An outcome of the Indian Act was the creation of Residential Schools.

Residential schools were part of a government-sanctioned policy which aimed for the assimilation and cultural genocide of Indigenous peoples, particularly Indigenous children, in Canada. Under the Indian Act, the Canadian government claimed the authority to create and operate residential schools with the purpose of removing Indigenous children from their families and communities. The Act allowed for the forced enrollment of Indigenous children into these schools, where they were subjected to forced assimilation, religious indoctrination, and the suppression of their Indigenous languages, cultures, and ways of knowing and being.

The Act provided the legal framework for the administration and funding of these schools, with the government working in collaboration with various religious organizations to run them. Indigenous children were often forcibly taken from their families and placed in these institutions, leading to profound trauma, loss of cultural identity, and disconnection from their families and communities.

Understanding the Indian Act is crucial to comprehending the long-term context and systemic factors that contributed to the creation and continuation of residential schools. The Act gave the Canadian government the authority to implement policies that were harmful and dehumanizing to Indigenous peoples, contributing to the intergenerational impacts of trauma and cultural loss experienced by survivors and their families.

By recognizing the role of the Indian Act in shaping the residential school system, we can better understand the magnitude of the injustices inflicted upon Indigenous children and communities. It is essential that settlers acknowledge and learn from this history to confront the legacy of residential schools, support healing and [re]conciliation efforts, and work towards building respectful and equitable relationships with Indigenous peoples in Canada.

Understanding the Indian Act also highlights the ongoing need for Indigenous self-determination and the dismantling of colonial policies and structures that continue to impact Indigenous communities today. By learning about the Act and its consequences, Canadians can take a more informed and empathetic approach to engaging with Indigenous histories, experiences, and continued fight for justice and equity.

This history of Residential schools is both traumatic and complex. We will look at some of these schools in some detail. For now, we will begin by looking at where these schools were located.

There are 139 Indian residential schools identified within the Indian Residential School (IRS) Settlement Agreement. This figure represents the residential schools that were funded and operated in whole by the federal government or in part by the federal government and a religious order.

It is important to note that the number of residential schools and the years they operated can vary in different records and sources. Additionally, some records may include day schools or industrial schools, which were similar to residential schools in their objectives and practices but operated on a slightly different model.

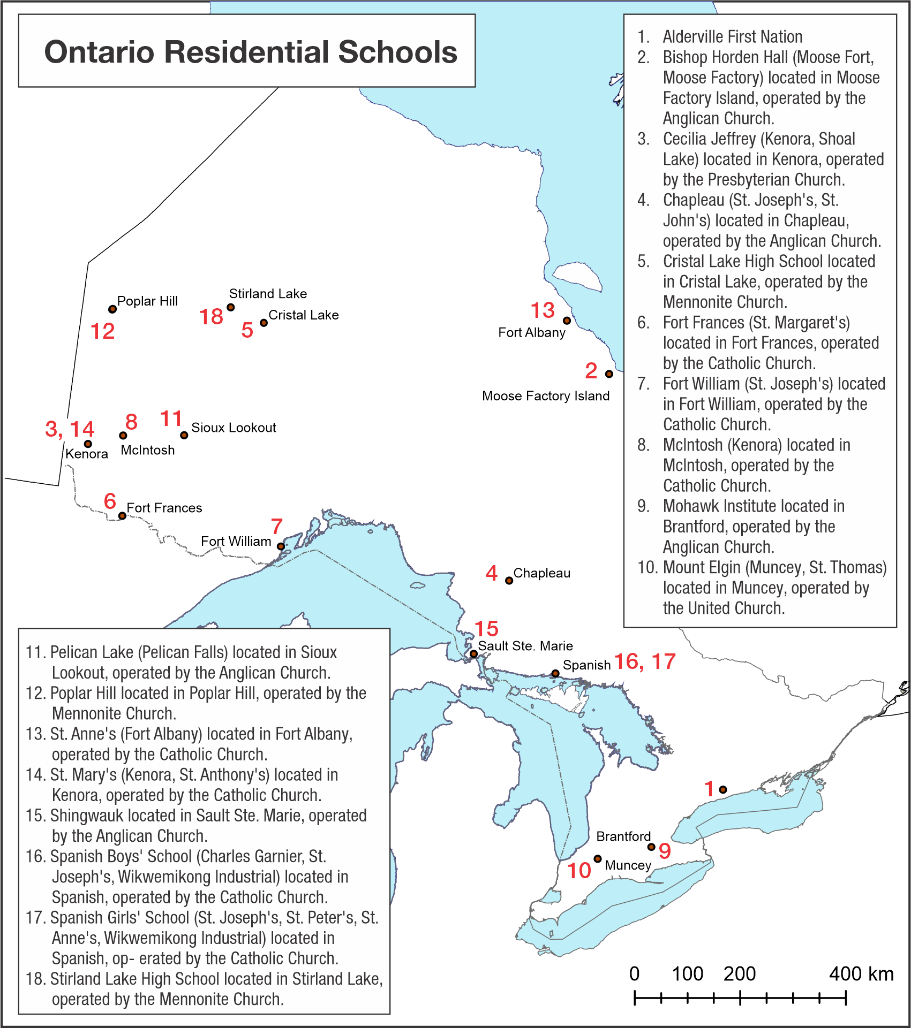

Let's look at a snapshot of where some of these schools were located. The map below shows us the location of schools in Ontario.

Credit: Geography, Environment and Geomatics, University of Guelph

Long Description

Map of showing the location of Residential Schools in Ontario:

- Alderville First Nation

- Bishop Horden Hall (Moose Fort, Moose Factory) located in Moose Factory Island, operated by the Anglican Church.

- Cecilia Jeffrey (Kenora, Shoal Lake) located in Kenora, operated by the Presbyterian Church.

- Chapleau (St. Joseph's, St. John's) located in Chapleau, operated by the Anglican Church.

- Cristal Lake High School located in Cristal Lake, operated by the Mennonite Church.

- Fort Frances (St. Margaret's) located in Fort Frances, operated by the Catholic Church.

- Fort William (St. Joseph's) located in Fort William, operated by the Catholic Church.

- McIntosh (Kenora) located in McIntosh, operated by the Catholic Church.

- Mohawk Institute located in Brantford, operated by the Anglican Church.

- Mount Elgin (Muncey, St. Thomas) located in Muncey, operated by the United Church.

- Pelican Lake (Pelican Falls) located in Sioux Lookout, operated by the Anglican Church.

- Popular Hill located in Popular Hill, operated by the Mennonite Church.

- St. Anne's (Fort Albany) located in Fort Albany, operated by the Catholic Church.

- St. Mary's (Kenora, St. Anthony's) located in Kenora, operated by the Catholic Church.

- Shingwauk located in Sault Ste. Marie, operated by the Anglican Church.

- Spanish Boys' School (Charles Garnier, St. Joseph's, Wikwemikong Industrial) located in Spanish, operated by the Catholic Church.

- Spanish Girls' School (St. Joseph's, St. Peter's, St. Anne's, Wikwemikong Industrial) located in Spanish, op- erated by the Catholic Church.

- Stirland Lake High School located in Stirland Lake, operated by the Mennonite Church.

List of Federal Indian Day Schools:

- There are 172 Day schools in Ontario listed on the Federal Indian Day School Class Action Schedule K document.

-

7 of which are still federally operated.

It is an uncomfortable truth for many settlers in Canada, but the experiences at these 18 schools in Ontario, like in other parts of Canada, is characterized by a history of trauma, cultural suppression, and the forced assimilation of Indigenous children. It is important to remember that throughout the province, and country, residential schools operated under the authority of the Canadian government and various religious organizations.

Children as young as five years old were taken from their families and communities and sent to these schools. The schools aimed to erase Indigenous languages, cultures, and traditions, with the objective of assimilating Indigenous children into Settler society. Many aspects of Indigenous cultures, such as languages, ceremonies, and spiritual practices, were forbidden, and children were often punished for speaking their languages or practicing their culture.

The living conditions in these schools were often harsh and deplorable. Children faced overcrowded and unsanitary living quarters, inadequate food, and a lack of proper medical care (Tennant, 2021). Physical, emotional, psychological, and sexual abuses were common, with staff using punishment and discipline as a means of control.

Children at residential schools were subjected to religious indoctrination, with Christian beliefs being imposed upon them. As a result, many children lost touch with their own spiritual beliefs and cultures.

The impact of the residential school system on Indigenous communities in Ontario has been profound and long-lasting. Many survivors and their families continue to grapple with the intergenerational trauma resulting from their experiences with these institutions. It is crucial to delve further into this experience to grasp the extent of the historic and ongoing harm caused by these institutions:

Forced Separation: Many Indigenous children were forcibly taken from their families and communities to attend residential schools. This separation was traumatic, as children were often forcibly removed from their families' care and placed in unfamiliar and hostile environments.

Loss of Cultural Identity: At residential schools, Indigenous children were stripped of their cultural identities. They were prohibited from speaking their languages, practicing their culture, or engaging in spiritual ceremonies. This loss of connection to their culture and heritage has had profound and lasting impacts on senses of self.

Abuse: Residential school survivors often recount instances of physical, psychological, and emotional abuse they endured at the hands of school staff. Punishments for speaking Indigenous languages or attempting to practice Indigenous cultures were common, leading to fear and feelings of shame among the children.

Neglect and Substandard Living Conditions: Many residential schools were poorly maintained, with overcrowded and unsanitary living conditions. Children often lacked proper clothing and were given inadequate food, resulting in malnutrition and health issues.

Religious Indoctrination: Christian religious teachings were imposed on Indigenous children, often without their or their families' consent. This religious indoctrination sought to replace Indigenous spiritual beliefs with Christian beliefs, further disconnecting children from their culture.

Loss of Family and Community Connections: Residential schools isolated children from their families and communities, cutting off essential support networks. As a result, children faced feelings of abandonment and a loss of their sense of belonging.

Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: Many children suffered sexual abuse and exploitation at the hands of school staff and administrators. The failure to protect the children from these abuses exacerbated their trauma.

Impact on Mental Health and Well-being: The cumulative effects of the residential school experience, including physical, sexual, psychological and emotional abuse, cultural loss, and separation from family, resulted in severe psychological trauma for many survivors. This trauma often manifested in mental health issues, substance abuse, and challenges in forming healthy relationships.

Inter-generational Trauma: The trauma experienced by survivors of residential schools has far-reaching consequences, affecting subsequent generations. Inter-generational trauma refers to the ongoing impact of the trauma on the children and grandchildren of survivors, perpetuating cycles of pain and healing.

In recent years, there have been efforts towards truth-telling and reconciliation, with the Canadian government acknowledging the historical injustices of the residential school system through official apologies and initiatives to support healing and cultural revitalization.

Much work remains to be done if we are to move past this dark legacy of our history. What we mean here by move past is not to forget about or leave behind these truths, but rather to sit with them, learn from them, and create new paths forward that aim to not repeat or further the cascading harms brought about by the residential school program.

Stop and Do

Stop and Do

What does the future look like – as noted in the section relating to the Indian act, that is not an easy question to answer. More so, perhaps, where the legacies of the Residential Schools are concerned.

As a country, we are moving towards a reckoning as to what those legacies mean to us collectively. Have you thought about it might on a more personal level? Take a moment and review Calls to Action in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission's report that relate to Residential Schools.

What do they mean to you? What are you prepared to act on?