In Canada, the Indigenous vs. Settler Timelines perspective refers to the historical timeline that encompasses the interactions and developments between Indigenous peoples and settlers (colonizers) from the time of European arrival to the present day. This perspective highlights the profound impact of colonization on Indigenous communities, including forced assimilation, displacement from ancestral lands, loss of language and cultural practices, and severe social and economic disparities. It also recognizes the resilience and ongoing struggles of Indigenous peoples to assert their rights, reclaim their cultural heritage, and achieve reconciliation and justice in the face of historical injustices. Understanding this perspective is crucial for acknowledging the complexities of Canada's history and fostering empathy and collaboration towards a more inclusive and equitable future.

At its core, the Indigenous vs. Settler timeline perspective in Canada is a journey through the historical interactions between Indigenous peoples, who have inhabited these lands for thousands of years, and the settlers who arrived from Europe and other parts of the world.

The timeline begins long before European contact when numerous Indigenous cultures thrived across the vast Canadian landscape. These diverse societies had rich traditions, languages, belief systems, and intricate connections with the land.

The turning point in this timeline occurred with the arrival of European explorers and settlers in the 15th and 16th centuries. This marked the beginning of significant changes as the newcomers sought to establish trade, colonization, and control over the land and resources. Interactions varied widely, with some Indigenous communities establishing alliances with settlers for mutual benefit, while others faced violent clashes and the loss of their territories.

As settlers expanded their presence in North America, conflicts and land dispossession increased. The 18th and 19th centuries saw the implementation of policies aimed at assimilating Indigenous peoples into European ways of life, including the establishment of residential schools where Indigenous children were forcibly separated from their families and culture, leading to immense intergenerational trauma.

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the Canadian government enacted policies like the Indian Act, which further controlled Indigenous lives and limited their autonomy. These actions severely impacted Indigenous societies, cultures, and governance structures.

In the latter half of the 20th century and into the 21st century, the Indigenous vs. Settler Timeline Perspective highlights a growing recognition of the need for reconciliation, truth-telling, and addressing historical injustices. Efforts have been made to acknowledge the past, seek truth, and establish pathways for healing and moving towards a more equitable future.

Throughout this timeline, Indigenous peoples have demonstrated incredible resilience, maintaining and revitalizing their cultures, languages, and traditional knowledge. They continue to advocate for their rights, including land rights, self-determination, and the preservation of their heritage.

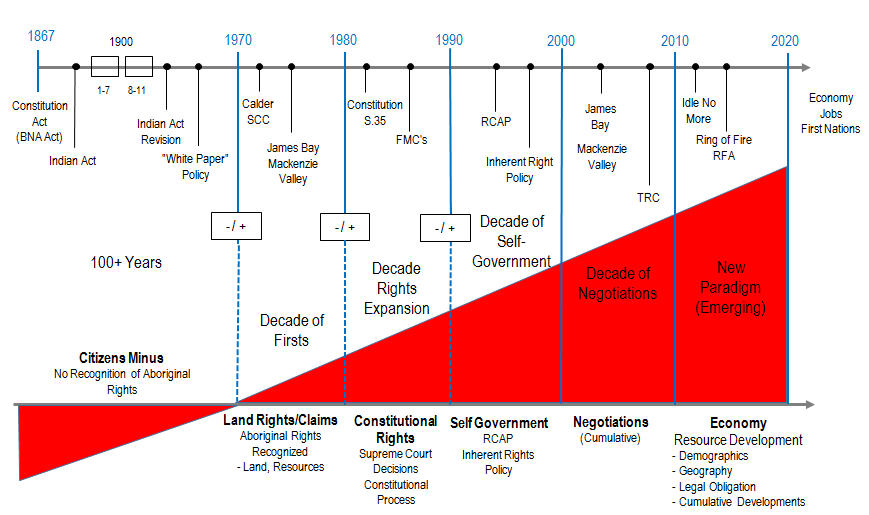

Let’s look at an example of some major historical events and milestones.

The interactive diagram below touches upon what was happening both in the Indigenous World and the Setter Occupation from Canada’s inception to the recent past. They are by no means the only important events, but they do help us better understand some of our history and why we may have different perspectives when it comes to timelines.

Timeline (events in order)

1867-1970

- Constitution Act

- Indian Act & Indian Reservation Act

- White paper policy

- Citizens Minus: No recognition of Indigenous rights

1970-1980

- Calder SCC

- James Bay Mackenzie Valley

- Decade of First: land rights / claims recognized (land, resources)

1980 – 1990

- Constitution S.35

- FMC’s (First Minister’s Conference)

- Decade of Rights Expansions: Constitutional Rights (Supreme Court Decisions, Constitution Process)

1990 – 2000

- RCAP

- Inherent Right Policy

- Decade of Self-Government: Self Government (RCAP, Inherent Rights)

2000 – 2010

- James Bay

- Mackenzie Valley

- TRC

- Decade of Negotiations: Negotiations (cumulative)

2010 – 2020

- Idle no more

- Ring of Fire

- New Paradigm (Emerging): Economy (Resource development, demographics, geography, legal obligations, cumulative developments)

2020 and Beyond

- Economy

- Jobs

- First Nations

Let’s look at some of the key events from the timeline in more detail:

1867-1970

- Constitution Act: This act established the foundation for Canada's government structure but did not initially recognize Indigenous rights or self-governance.

- Indian Act and Indian Reservation Act: These laws granted the Canadian government significant control over Indigenous peoples' lives, lands, and resources, leading to cultural suppression and land dispossession.

- White Paper Policy: Proposed in 1969, this policy aimed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream Canadian society by eliminating their distinct legal status, but it faced strong opposition from Indigenous communities.

1970-1980

- Calder SCC: The Calder case in 1973 brought attention to the issue of Indigenous land rights and recognition.

- James Bay and Mackenzie Valley: These significant land claims settlements established precedents for recognizing Indigenous rights to land and resources.

1980-1990

- Constitution S.35: Section 35 of the Constitution Act in 1982 recognized and affirmed existing Aboriginal and treaty rights, a pivotal moment for Indigenous rights.

- FMC's: Provision were made for a series of First Ministers Conferences "to identify and define" Aboriginal and treaty rights.

- Decade of Rights Expansions: Constitutional Rights (Supreme Court Decisions, Constitution Process): Land claims and self-government agreements negotiated during this decade aimed to address historical injustices and provide Indigenous communities with greater autonomy.

1990-2000

- RCAP (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples): This commission, established in 1991, extensively explored Indigenous issues and made recommendations for reconciliation and self-determination.

- Inherent Right Policy: Recognized in 1995, this policy acknowledged Indigenous peoples' inherent right to self-government and autonomy.

2000-2010

- TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission): Formed in 2008, the TRC examined the history and legacies of the residential school system and sought to promote healing and reconciliation.

- James Bay and Mackenzie Valley: Ongoing land claims and resource development negotiations continued during this decade.

2010-2020

- Idle No More: A grassroots movement that began in 2012, advocating for Indigenous rights, sovereignty, and environmental protection.

- Ring of Fire: Refers to a potential mining and infrastructure development project in Ontario that has significant implications for Indigenous communities.

- New Paradigm (Emerging): This period saw increased focus on economic development, resource development, and recognition of Indigenous contributions to the national economy.

2020 and Beyond

- Economy, Jobs, First Nations: Current and future considerations include the importance of economic opportunities, job creation, and the role of First Nations in shaping sustainable development.

Stop and Reflect

Stop and Reflect

Think about what you have learned about in terms of the varying perspectives of a timeline in Canada’s history thus far. Now, pick one or two of the key events from the timeline above. From an Indigenous perspective, can you guess or identify why the event or event are important?

Obviously, there is no one single correct answer – but when you are done collecting your thoughts, click on “Some thoughts” and compare your ideas with those below.

Some thoughts

1867-1970:

- Constitution Act: This foundational legislation marked the beginning of Canada as a nation but initially excluded any explicit recognition of Indigenous rights and self-governance. This omission set the stage for a long history of marginalization and discrimination.

- Indian Act and Indian Reservation Act: These laws drastically impacted Indigenous peoples' lives, as they granted the government extensive control over Indigenous lands, resources, and cultural practices. The Indian Act, in particular, imposed a system of governance that undermined traditional Indigenous leadership structures.

- White Paper Policy: The proposed White Paper Policy in 1969 aimed to assimilate Indigenous peoples into mainstream Canadian society, negating their special legal status and undermining their inherent rights. This policy sparked strong opposition from Indigenous communities who saw it as an erasure of their distinct identities and cultures.

1970-1980:

- Calder SCC: The Calder case was a landmark moment, bringing the issue of Indigenous land rights to the forefront and laying the groundwork for future land claims negotiations.

- James Bay and Mackenzie Valley: These land claims settlements were significant victories for Indigenous peoples, as they recognized Indigenous land rights and established models for self-government and resource management.

1980-1990:

- Constitution S.35: The recognition of Aboriginal and treaty rights in the Constitution Act of 1982 was a crucial turning point, affirming Indigenous peoples' rights to land, resources, and self-determination within Canada's legal framework.

- FMC's were complicated – there were differing opinions between those First Nations who had participated in the Numbered Treaties and those who depended on Aboriginal title.

- Decade of Rights Expansions: Constitutional Rights (Supreme Court Decisions, Constitution Process): These agreements provided Indigenous communities with greater control over their lands and resources, enabling them to shape their futures more independently.

1990-2000:

- RCAP (Royal Commission on Aboriginal Peoples): The RCAP was a groundbreaking initiative that brought attention to the complex issues facing Indigenous communities, including the legacy of residential schools, cultural preservation, and the need for reconciliation.

- Inherent Right Policy: The acknowledgment of Indigenous peoples' inherent right to self-government was a significant step towards recognizing their inherent sovereignty and right to shape their governance systems.

2000-2010:

- TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission): The TRC's work shed light on the dark chapter of the residential school system, acknowledging the immense harm caused and emphasizing the importance of reconciliation and healing.

- James Bay and Mackenzie Valley: Ongoing negotiations and agreements during this period demonstrated the continuing efforts to address historical injustices and create more equitable relationships with Indigenous communities.

2020 and Beyond:

- Economy, Jobs, First Nations: These considerations highlight the growing recognition of Indigenous contributions to the economy and the importance of fostering sustainable economic development that respects Indigenous rights and land stewardship.

These key events hold profound significance for Indigenous Canadians as they represent steps towards recognition, justice, and autonomy. They are essential in acknowledging the historical injustices faced by Indigenous peoples and serve as guideposts for a future built on respect, reconciliation, and the flourishing of Indigenous cultures and communities.

Common Mistakes

Here are some do and don’t lists for well-meaning individuals wanting to engaging with Indigenous Peoples, Knowledge Systems, and cultures. How many of these have you participated in, were subject to, or experienced?

Warning

Warning

Before acting, take a moment to think about your intentions vs. your knowledge and ability to act.

The danger of not having enough knowledge about Indigenous cultures and histories is that you may unintentionally perpetuate stereotypes, misrepresentations, and harmful practices. Without proper understanding, you might engage in cultural appropriation, trivialize sacred traditions, or unknowingly reinforce harmful colonial narratives.

By not having enough knowledge and awareness, you could inadvertently cause emotional distress and perpetuate historical inaccuracies and harms in your interactions with Indigenous peoples in Canada. This can lead to a perpetuation of harmful attitudes and behaviors that contribute to the marginalization and erasure of Indigenous peoples' identities, cultures, and histories. Even if this was not the outcome you intended.

It is essential to approach teaching others about and interacting with Indigenous peoples in Canada with sensitivity and cultural competency. Be aware of where you are at in your journey and really think about if you are ready and able to achieve the outcome you are seeking.

In the end, our aim should be to build bridges of understanding, dispel stereotypes, and promote genuine reconciliation and respect for Indigenous peoples' diverse cultures and histories. The realization of this goal requires a commitment to continuous learning, self-reflection, and acknowledging the diverse experiences and perspectives of Indigenous Peoples.

Important Considerations

- Don’t single out Indigenous children, ask them to describe their families’ traditions, or their cultures.

- Don’t assume that there are no Indigenous people/children in your class/ work or neighborhood.

- Do look for books and materials written and illustrated by Indigenous people.

- Don’t use story books that show non-Indigenous children “playing Indian.”

- Don’t use picture books by non-Indigenous authors that show animals dressed as “Indians.”

- Do avoid arts and crafts and activities that trivialize Indigenous dress, dance, or ceremony.

- Don’t use books that show Indigenous people as savages, primitive crafts people, or simple tribal people, now extinct (i.e., historicizing narratives).

- Don’t have children dress up as “Indians,” with paper-bag “costumes” or paper-feather “headdresses.”

- Don’t have them make “Indian crafts” unless you know authentic methods and have authentic materials.

- Do make sure you know the history of Indigenous peoples, past and present, before you attempt to teach it.

- Don’t use materials which manipulate words like “victory,” “conquest,” or “massacre” to distort history.

- Don’t use materials which present only those Indigenous people who aided Europeans as heroes.

- Do use materials which present Indigenous heroes who fought to defend their own people.

- Do discuss the relationship between Indigenous peoples and the colonists and what went wrong with it.

- Do use respectful language in teaching about Indigenous peoples.

- Don’t portray Indigenous peoples as “the first ecologists.”

- Do invite Indigenous community members to the classroom.

- Do offer them an honorarium. Treat them as teachers, not as entertainers.

- Don't assume that every Indigenous person knows everything there is to know about every Indigenous Nation.

Note: Adapted from www.oyate.org, a Native organization “working to see that our lives and histories are portrayed honestly”

Phew! That was a lot! How many have you experienced? Most Indigenous peoples will have experienced all of the ‘Don’ts’ and not enough of the ‘Do’s.

Warning

Warning

Take a moment and revisit the list above. Select one or two of the “don’ts.” That you’d like to work with on your own to better understand the teaching.

Some thoughts:

It’s not enough to be told what not to do. Following a list without understanding the meaning behind it will not allow you to develop the skills, knowledge, and attitude to be successful in various social and professional settings, where contexts can shift or change. You need to understand why you should not do something if you are going to be able to act upon these ideas in varied circumstances.

So, consider the impact behind the “don’t” from both an historical and contemporary perspective. Think about what is going on and answer to yourself why such a caution against an action or idea exists.